Introduction

The check engine light came on, and OBD code read DTC P0128. Quick googling shows that this is coolant (antifreeze) temperature not rising fast as expected. Possible reasons could be:

- Stuck open thermostat (common). The thermostat sits between engine block and radiator. It is closed when coolant is cool (e.g. < ~200°F), so the engine would warm up the coolant inside engine block first. When the engine block is hot enough for best working condition, the thermostat opens up, water pump pushes the coolant through radiator and thermostat, then back to engine to cool down engine. If the thermostat is stuck open, coolant circulates through radiator before the engine is hot, causing P0128 DTC.

- One way to confirm this problem is by looking at the water/coolant temperature meter at dashboard.

- If thermostat works correctly, the temperature should rise to mid level (1/2) after a few minutes of engine running. Then thermostat would open. If you check underhood, before that time the coolant pipe coming from radiator to thermostat housing should stay cool, and after thermostat opening up, hot coolant would flow through radiator to the pipe, and you should feel it being hot.

- If thermostat is stuck open, the water temperature may never come to mid-level. For my car, it never got over 1/4 level. This is therefore very likely the reason.

- One way to confirm this problem is by looking at the water/coolant temperature meter at dashboard.

- Faulty coolant temperature sensor (sometimes) or sensor connector. On the engine front near the battery, there’s temperature sensor the ECU reads to monitor coolant temperature. This connects to dashboard temperature meter, and is used by ECU to control cooling system. If this does not work, ECU gets wrong information and may cause P0128.

- Air trapped in cooling system near thermostat causing it to malfunction (rare). This may be due to reservoir coolant running low, so cooling system sucks air into it.

First Try: Top Off Reservoir

For my car, I first checked the reservoir coolant level, and it was even lower than MIN. So I added coolant to the reservior to MAX with a funnel. This car uses MOPAR OAT coolant. I could not find exact coolant, so I used AutoZone universal OAT (yellow) 50/50. The coolant reservoir cap is near the battery. I cleared the DTC with OBD reader. After running the car for 20 miles or so, P0128 came back. Obviously, just adding coolant to reservoir did not fix the cooling system issue.

Second Try: Bleed Air

Changing either thermostat (with or without housing), or temperature sensor, is not trivial work. I’d like to try to bleed air from the cooling system, given that reservoir was too low and air might have been trapped.

The bleed screw is on the thermostat housing, which is on the engine block next to the air filter. I opened the radiator cap, and used a long phillips screw driver loosened the bleed screw by aboud 3 turns. Initially it spit some bubles, then quickly a small steady stream of coolant came out. The coolant level in radiator also dropped. I then tightened the bleeding screw, topped off the coolant at radiator with a funnel and capped it.

After running the car for 20 miles or so, P0128 came back. It was not caused by the small amout of trapped air.

Third Try: Replace Thermostat

Now it became serious work. There are plenty of YouTube videos on how to replace the thermostat/housing, and you can also ask ChatGPT to get a detailed list of steps to follow.

I ordered an after-market Dorman theremostat with housing and gasket ($18) and hose clamp pliers at Amazon. I also ordered an OSKYUO coolant temperature sensor ($9) and EPAuto Spill Proof Radiator Coolant Filling Funnel Kit, but it turned out unused.

Terse summary:

- Make sure engine is off and cool.

- Wear gloves to protect hands from scratching and toxic chemicals.

- Unscrew 13mm nut holding steering fluid reservoir

- Unlock 3 clamps locking upper half of air filter housing.

- I tried to detach the big air hose from the housing, but in vain. Too tight. Not a problem to keep it there.

- The PCV hose (small) is easy to detach.

- Remove air filter (good chance to replace if too dirty). This gives the chance to inspect how to remove the lower half of the air filter housing. I wiggled it back and forth and it did not come off easily. Finally after I removed the air filter, I could see some plastic anchor latches at the housing bottom. Directing my force around that, the lower housing came off.

- I used some wires/hooks to pull the upper housing and steering fluid reservoir away from obstructing the working area.

- The thermostat housing is attached to the engine block with two 10mm screws. The lower screw is invisible and you have to hand feel it, and it’s a bit hard to access even with the air filter housing removed due to limited clearence. You must use the rachet with very short adaptor/extension (but not too short).

- Put an oil drain pan under the car to catch coolant. ChatGPT says about 1 gallon of coolant may come out after detaching thermostat housing.

- Unscrew the 10mm screws carefully with rachet. Once it’s loose, hand unscrew them. Pull the thermostat housing off engine carefully. Coolant would leak from the engine block. It turns out to be about half gallon or so coming out.

- I tried to detach the radiator hose from the theremostat housing. Even with a hose clamp pliers opening the clamp, and using a screw driver to peel the hose from housing, I could only turn the housing around hose, but it would not come off. Too tight.

- So I gave up on that, and instead just replaced the thermostat only. In the new housing, use pliers to turn the holding lock counterclockwise, so it comes off with the spring, then just take the thermostat. Similarly do the same on the old housing to remove thermostat. Be care to hold the spring so it does not shoot away. I only swapped the thermostat, and reuse the old spring and lock, because the new lock does not seem to fit very well in the old housing.

- Push the thermostat housing the engine block, and tighten the two 10mm screws. Do not overtighten, or the plastic housing can break.

- Move the hose clamp to the original location and unlock the hose clamp pliers. This makes sure it does not leak.

- Bleed air and add coolant. Loosen the bleed screw by 3 turns, and add coolant to radiator. The air comes out and after a while the steady stream of coolant comes out. Then tighten bleed screw.

- I used a funnel to rinse the messy coolant around the thermostat housing and below with clean water.

- Install the air filter housing and air filter, and the steering fluid reservoir.

- Add coolant to top of the radiator. It may burp, just add more coolant then.

- With radiator cap open, turn on engine. The radiator coolant level may rise and overflow. It may also burp. If the coolant level drops, add more coolant.

- I ran the engine for about 15 minutes and the temperature reached mid-level. This was a good sign. Then obivously the theremostat opened, because I saw the coolant level drop a lot at radiator (before that it just overflew and burped intermittently). After running engine for 10 more minutes, with more burps, overflow, and adding more coolant, I capped the radiator cap and turned off engine. The coolant temperature has been quite steady at min level.

- Clean the DTC code.

- That’s it for the day. I will check later after running the car on road, for radiator level (when cool), reservoir level, and DTC.

Pictures

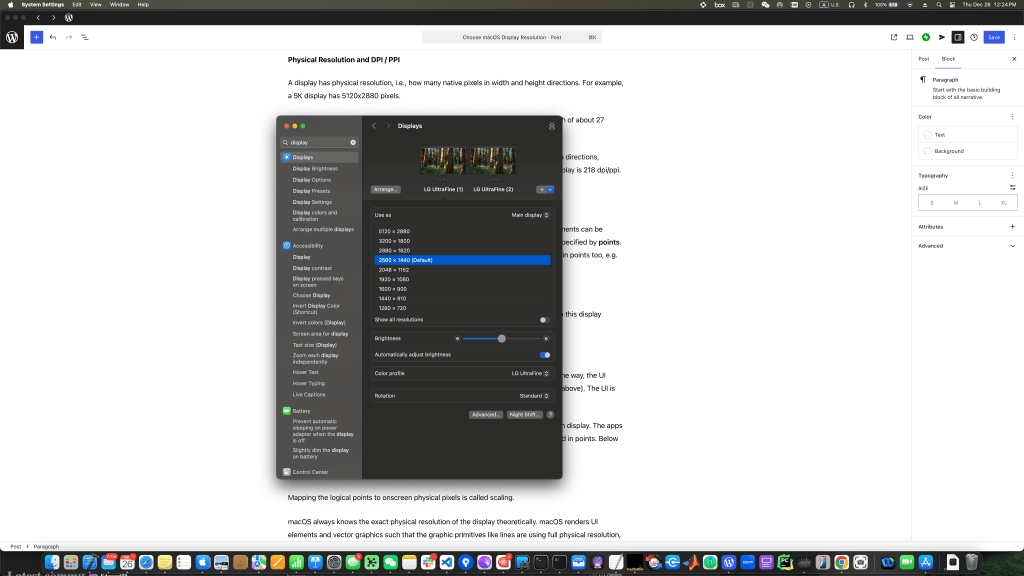

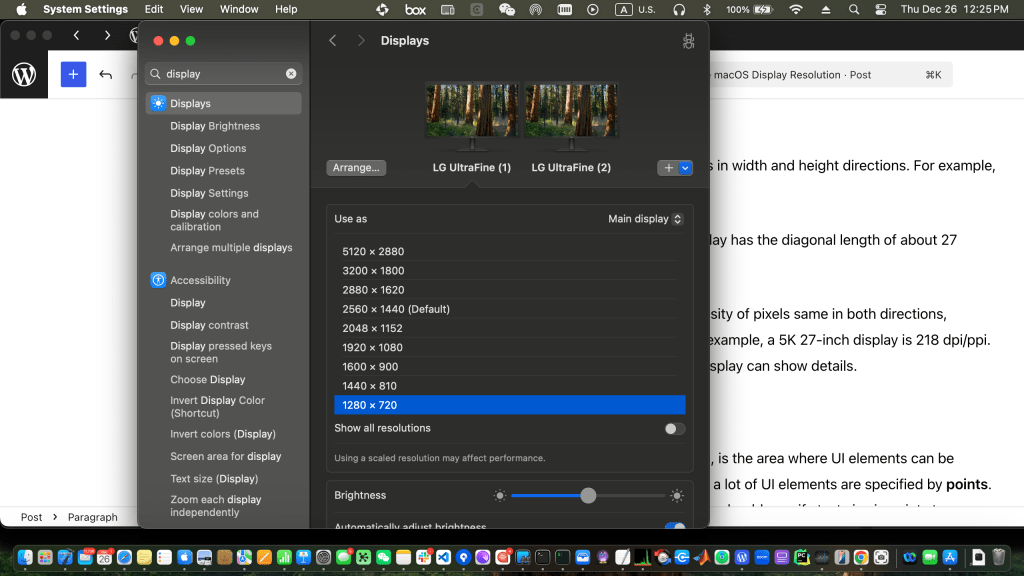

Above: only reaching 1/4 of water temperature meter is problematic. Stable running engine should see about 1/2 level.

Above: what’s under the hood.

Above: propping and hooking for easier access to the thermostat housing.

Above: close up on the thermostat housing.

Above: new thermostat (inside spring coil), spring coil, metal lock, and plastic housing. Also notice the phillips bleed screw.